When Saints Row (2006) begins, the player character finds themself in the crossfire of a local turf war between three rival gangs. After being saved by a fourth group called the 3rd Street Saints, they embark on a journey to wrest control of the streets of Stilwater from the bloodthirsty gangs in the name of the slightly-less-bloodthirsty Saints. It’s a timeless tale of grit, betrayal, and triumph—a ragtag group of outcasts trying to carve out a living outside the law.

When Saints Row IV (2013) begins, the same protagonist, leading the now-paramilitary Saints in a counterterrorist operation alongside MI-6, rides a nuke into the stratosphere, disarms the nuke midair, crash-lands in the Oval Office, becomes President of the United States, and has their consciousness uploaded to a Matrix-type simulation after being abducted by aliens during an invasion. And that’s the prologue.

How did we get here? And where are we going next? With the new reboot on the horizon, it’s worth investigating how a franchise grounded in a modestly heightened reality (by video game standards, at least) took such a turn for the absurd, and whether its streak of turning everything up to 11 will (or should!) continue in future games. In other words, will Saints Row (2022) more resemble the first two entries, focusing on the lives of a common street gang? Or is it going to be one of the weird ones?

Where We Started

The original Saints Row proved a worthy challenger to Grand Theft Auto’s monopoly on the open-world street crime genre of games. Often called a clone of that older franchise, it nevertheless managed to set itself apart from GTA with its even more irreverent sense of humor and unpolished, salt-of-the-earth gangster narrative. GTA never really attaches you to one faction or another, preferring to let the player take to the streets as a lone wolf without much in the way of allegiances. Conversely, Saints Row is all about devoting your life to the titular gang, and it’s that dedication to an often-dysfunctional found family that allowed the first game to stand on its own merits.

The game is set in a silly but more-or-less realistic world where the rules of physics have at least some presence. Galvanized by their near-death experience, your silent character immediately drops whatever life they had going on to jump into the 3rd Street Saints, an up-and-coming gang which promises to be a little less wantonly violent than its competitors.

At its heart, it’s the classic underdog story championed by countless gangster flicks before it. From a gameplay perspective, it’s a serviceable experience. It does sport somewhat dodgy driving controls—less than ideal for its urban setting—but it’s otherwise successful in its emphasis on auxiliary content being used to advance the main plot, a very deliberate design feature that departed from genre conventions that made side missions a distinctly optional part of the experience. It was a critical and commercial success, enough of one that publisher THQ ordered a sequel almost immediately.

That sequel, Saints Row 2, went just a little crazier than its predecessor. It began to cleave more to the outrageous setpieces and dick jokes that would come to form the basis of the franchise’s identity. While their main competition headed in a more realistic direction with Grand Theft Auto IV, Volition took the opposite approach, aiming for a more cartoonish, self-aware tone. They recorded twice as much dialogue for the game as they had with the first, allowing for greater characterization of the main cast and more opportunities for verbal slapstick. They gave the protagonist (soon to be known simply as The Boss) speaking lines. They allowed the game to stay bright and colorful, which served to keep the enemy gangs visually distinct and personalize the game’s world in contrast to GTA’s flattening of hues.

The result is an inarguably more refined gameplay experience with some notable tonal dissonance between the wacky antics and the mostly serious plot, which is fittingly centered around a struggle over the Saints’ identity as they pursue revenge against a new triad of would-be usurper gangs. Despite its occasionally uneven storytelling, all its shortcomings paled against the fact that the game was just plain fun, and that’s what mattered most to audiences. The game cemented Saints Row as a tentpole franchise for THQ, a company that was alarmingly low on tentpole franchises. (More on that soon.)

Where We Went

But if the second game stuck a toe into the franchise’s signature ridiculousness, its follow-up swan-dove into it–and what a splash it made. Saints Row: The Third is a fever dream of bombastic action and shameless self-reference. It’s got no shortage of personality, to say the least. In fact, the team actually decided on a unifying symbol for the game’s personality: the Dildo Bat, a weapon that… is a dildo bat. Hey, Saints Row’s been called a lot of things, but “modest” isn’t among them.

This is the first of The Weird Ones.

Development on Third was a rocky process, with a publisher in its death throes and a creative team composed primarily of newcomers to the franchise. In such an environment, it might be tempting to stay the course and avoid changing what’s been proven to work. The Third team, uh… did not do this.

I’ll never forget the sequence in which the main character skydives from a chopper and parachutes onto a skyscraper rooftop party while Ye’s Power (expertly timed to the jump, natch) plays in the background. Even though you have complete control of your character’s movement, the scene manages to feel finely choreographed, each beat in the action introduced by a new instrument or verse, each lyric thematically tied to the notion that you’re a bad person doing something extraordinary. It’s quite possibly the single best needle drop in video game history.

That power fantasy (ha) is the beating heart of the game, and while few other moments are quite as elegantly crafted, there’s no denying that the whole experience absolutely crackles with energy. Where past entries frequently switched tonal lanes, Third commits to full-on ridiculousness. It leaves no question that the series has embraced insanity creep, the same momentum of escalating stakes and the gradual phasing-out of physical concepts like gravity that the Fast franchise and even the MCU have found success in leaning into.

The Saints are now the equivalent of criminal influencers, using crime to boost their brand’s popularity. They rob banks as PR stunts, produce movies about their own exploits, and sell Saints merch to the people whose money they’re stealing. They’ve grown overly comfortable with the excesses of fame, and their enemies capitalize on their complacency.

Likewise, the gameplay crams in as many opulent ideas as its poor Havok engine can fit. There’s a new RPG-inspired leveling system with skill and weapon upgrades. There are robust customization options, many of them scatological in nature. There’s a surprising array of celebrity cameos, including Burt Reynolds as himself. There are gag weapons, elaborate monuments to toilet humor, and just so many things shaped like dildos (or maybe they’re big dildos being utilized for non-dildo functions—it’s hard to say for sure). Despite plenty of chaff, most gamers would probably describe it as their quintessential Saints Row experience, if only by sheer content alone. It’s got everything you could ask for on a studio budget in 2012.

And they had the resources to play around with: THQ, on the verge of bankruptcy, was throwing money at Volition to turn Saints Row into a bona fide AAA franchise in a desperate attempt at financial recovery. Looking back at the plot of the game—the Saints becoming a victim of their own excesses, stripped for parts by an evil Syndicate and left to crawl their way back to the top—it becomes an almost eerie metaphor for the massive changes going on behind the scenes, to the point where it’s hard to imagine at least some of it isn’t an imitation of reality, conscious or not. Here was THQ’s last, best hope, fiddling while Rome burned.

A planned expansion for the game called Enter the Dominatrix started development alongside preliminary work on a fourth mainline title but, desperate to calendar a launch title, THQ pushed for Volition to merge the two projects. Shortly thereafter, Volition was sold to Koch Media, and the studio announced Saints Row IV would be published by Deep Silver. The whole studio dove into the next installment with the goal of pushing the envelope even further than Third had.

And I guess, technically, they did.

Where We Ended Up

There’s no getting around it: Saints Row IV is a clusterfuck. It’s absolutely The Weird One. Whatever executive restraint previous entries had been afforded must have been on THQ’s account because—hoo boy—we’ve officially jumped the shark here. The “plot” of IV involves the Boss becoming President of the U.S. and fighting an alien empire from a Matrix-like simulation of Steelport. Oh, also, the Boss has superhuman abilities like pyrokinesis and superspeed, all of which are so overpowered that there’s absolutely no reason to make use of all the unique weapons and customizable vehicles the game inexplicably provides you with. The urban sprawl of Steelport suddenly feels a lot smaller when you can jump across the map with a couple button presses.

And that’s just one of many ironies that make IV ring so hollow compared to its predecessors. Features like the homie support system, a mainstay of the series that allows you to call in fellow Saints as backup, are utterly vestigial when you can spam enemies with remote explosions before leaping to the other side of the city. The design philosophy of “putting everything in” has extended beyond mere content into actual gameplay systems. The game shamelessly apes and satirizes mechanics from its contemporaries. There’s a Call of Duty-parodying slow-mo door breaching sequence in the first five minutes. The god-like traversal and combat abilities are more than reminiscent of Infamous or Prototype. The tower-scaling territory control missions are a copy of the same system popularized by Far Cry. The player hub, a spaceship floating amid the wreckage of Earth, is nearly identical to the Normandy in Mass Effect, with the onboard simulation pod bearing a striking resemblance of Assassin Creed’s Animus. It’s a pastiche of every idea, original or not, and it doesn’t pretend to be anything else.

But if the point of pastiche is to comment on its disparate elements by exploring how they interact, what is Saints Row saying about its own bizarre amalgamation? Is it a celebration of the medium’s tendency to extravagance? Is it a critique on the vapid nature of AAA content? Or maybe it’s simply an exercise in endless pop culture reference, a masturbatory challenge to the audience à la Ready Player One.

Third pruned most of its extraneous features late in development, but IV seems to have taken no such measures. It feels like nothing was cut; if something didn’t fit, it was dialed up to 11, matching the rest in flamboyance and audacity, if nothing else. Unfortunately, the best songs aren’t the ones where every part is unbearably loud in the master. At that point, they all fade into a single, featureless noise: overwhelming and unfocused.

Saints Row IV received a handful of DLCs, each more ludicrous than the last, but there was a sense that audiences felt Volition had overplayed their hand. Reviews of the game were much less charitable than those for Third, now bemoaning the same ostentation which had been part of the latter’s charm. Our eardrums had finally blown out. For the next six years, Saints Row faded into memory, a high-pitched ring to be eventually tuned out altogether.

That is, until 2019, when Volition announced they’d be taking another swing at it.

Where We’re Headed

Well, the dildo bats are gone.

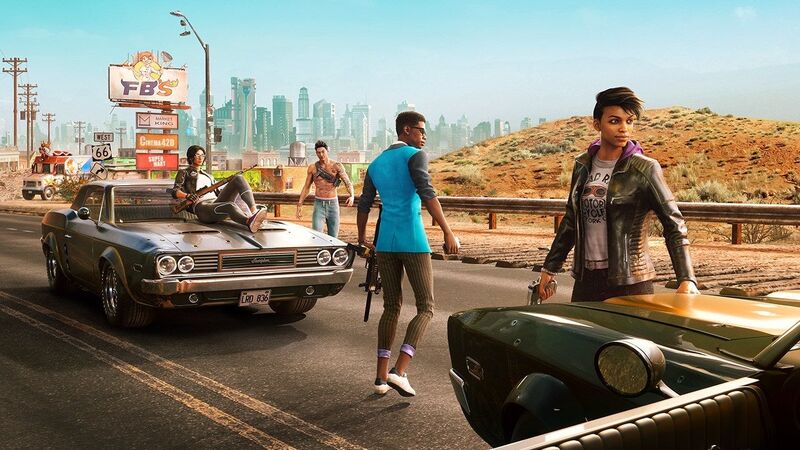

Early footage and testimonies by gaming journalists seem to suggest that Saints Row (2022), a reboot of the franchise, is taking a more modest approach (relatively speaking). The story takes place in a new city, Santo Ileso, and chronicles the rise of a street gang called—you guessed it!—the Saints. This gradual ascent from humble beginnings is in stark contrast with the Saints mega-conglomerate and spacefaring shenanigans in IV (and Santo Ileso isn’t an in-universe simulation, as far as we know). It’s an approach that harkens back to the series’s roots, which many will welcome.

But that’s not to say it’s lost all its flash. Customization is still front and center, with a plethora of unique outfits and weapon styles in addition to what might be the most robust character creation tool to date. Driving has been completely rebuilt, morphed into a system that encourages players to use their cars as weapons. Demos show collisions with plenty of extra heft, so that even sideswipes can cause cars to launch into the air Burnout-style. A new wingsuit option promises players some extra mobility without quite going as far as turning the character into Superman.

There’s a general consensus among those who’ve played or watched extensive gameplay that the game’s tone (and its relationship with the laws of physics) lands somewhere between Saints Row 2 and Saints Row The Third. This seems to be the sweet spot for many gamers: plenty of weird without dumping the whole can in.

Overall, this seems like a step in the right direction. Grounding the franchise in a slightly more realistic place stands to benefit it. Now that we’ve seen what video game worlds look like when there are no rules, we can see what they look like when we impose specific and careful limitations on them. After all, there’s something compelling about the discovery of what’s possible when not everything is.

Saints Row’s return is a welcome one, and time will tell how it measures up to its legacy. It may be a challenge for the series to reassert itself as a force of irreverence and bravado, but if they manage to pull it off, it’s sure to be one for the books. And, hey—maybe we’ll get that dildo bat in the DLC.