Being in the right place at the right time can mean the difference between success and failure. Such is the case when Balsa, a wandering, spear-wielding bodyguard, saves Prince Chagum, son of the emperor of Shin-Yogo, from a near-fatal accident when he falls off of a bridge into a surging river.

It’s a dramatic start to Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit, an anime series that goes on to explore parallel magical worlds, betrayal and treason in mythical kingdoms, and attacks by horrific, otherworldly monsters. It has all of the pieces that make an anime classic, stunning visuals by a well-known animation studio, a rich and vibrant world, and characters with satisfying emotional depth. Moribito accomplishes more in a single season of 26 episodes than many series can in multiple seasons, and it deserves a place of honor in the pantheon of great anime.

An Asian Fairy Tale

The overall premise for the series is simple enough: Balsa must defend Chagum from assassins sent by his father, the Mikado (think “Emperor Priest”). Chagum carries within him a piece of a water spirit, and the Mikado’s advisors believe it might be a demon that could bring ruin to the entire nation. By the end of the series, we know the truth of the spirit’s origins, and the full story of the founding of the nation of Shin-Yogo.

However, it’s not the grand scope of these issues that gives the series such impressive heft, but the quiet, intimate moments between the characters and the exploration of emerging, established, and changing relationships. This finesse can be traced to the quality of the animation and the superb writing in the source material.

Moribito is adapted from the first novel in a series of books by Nahoko Uehashi. Her Moribito books are a smash hit in Japan, having sold well over a million copies in print. Production I.G, the storied animation house behind Ghost in the Shell: Standalone Complex, adapted the book. Kenji Kamiyama, who also directed Ghost in the Shell: SAC, directed all of the episodes of Moribito.

In an interview about the anime adaptation, Uehashi described her book as a uniquely Asian fairytale, as opposed to a fantasy inspired by Western myths and legends.

“If there are any subtle differences [from Western fantasy titles] it’s the fact that it was created by a Japanese-born, Japanese author. It came from within me. A fantasy tale with an Asian flavor.”

The world Uehashi created is rich with references to the unique cultures of the region in which she lives. The Shin-Yogo empire is distinctly Japanese in flavor, and Balsa’s homeland of Kanbal resembles the Tibetan or Nepalese highlands. The native Japanese religion of Shinto, too, is reflected heavily in the cultural practices of the Shin-Yogo and the Yaku reverence for the natural world. Its greatness, however, hinges primarily on the very human relationships it shows.

A Bond Between Two Heroes

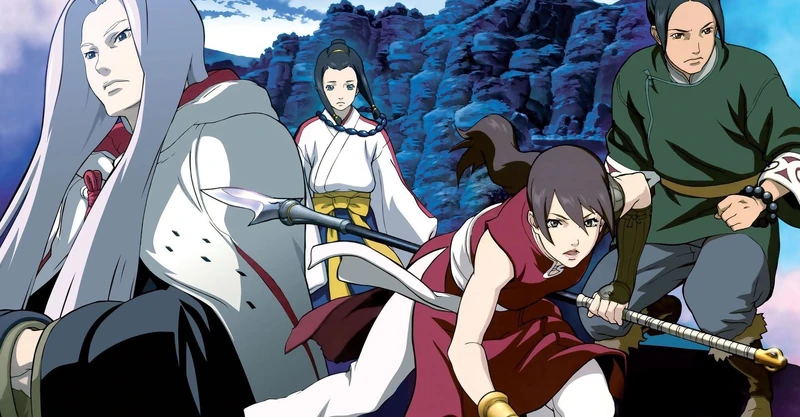

At the heart of the series is a very uncommon relationship: the bond between the gruff, combative Balsa and her ward Chagum, a gentle-natured prince whose older brother is set to inherit the throne. Balsa is not the kind of woman you usually meet in an anime. She more closely resembles a wandering samurai from a Japanese period film or a warrior from a Wuxia tale, like the Samurai from Yojimbo or Shu Lien from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, than she does your typical anime heroine.

Chagum, by contrast, is a model prince. He is supremely empathetic, attuned to the moods and emotions of those around him, and shows astounding care for animals and those less powerful than he. He certainly has fish-out-of-water moments — his stilted, formal speech gives away his noble origins to anyone who hears him say so much as “hello.”

Unsurprisingly, Chagum’s initial contact with Balsa is confrontational. There is an uncertainty that passes between them which borders on distrust. Balsa finds Chagum’s stamina disappointing, and Chagum finds Balsa boorish and rude. That standoffishness doesn’t last terribly long. After Balsa nearly dies fighting off some of the Mikado’s assassins, Chagum is fascinated by this total stranger’s ferocity and willingness to risk death to defend him. Balsa likewise is impressed by Chagum’s emotional resilience and how quickly he toughens up.

The relationship between the two is never static. It follows an arc that allows them to feel both affection and disappointment with one another without becoming saccharine or cheesy. At first, Balsa isn’t driven by some maternal instinct to care for Chagum simply because he is a child. It’s just another job, one she was put up to by Chagum’s real mother, and for which she resents the empress because of the upheaval it means in her own life. It doesn’t matter if she likes Chagum or not; one gets the sense that she would defend him just as fiercely even if she couldn’t stand him. Her affection for the young prince comes later, and it comes strong. Chagum wins it by trying desperately to understand more of the world around him, and perhaps charming her with his intense affection for things as simple as porridge, or frogs leaping to catch flies in the rice paddies near their hideout.

Similarly, Chagum grows to understand Balsa’s desire to protect him as a way for her to better understand her upbringing. He also learns his guardian’s heart so well that he coaches her on engaging with her own feelings more honestly. The mutual respect between them is an honest representation of what the relationship between parent and child can be, despite them sharing no bond of blood.

It’s clear, by series’ end, that Balsa and Chagum have both grown immensely from their time together. Chagum has become a better leader, prepared to assume a grander role in his kingdom, and Balsa has embraced the tragic details of her past, moving on to yet another adventure. Watching the bond between Balsa and Chagum develop is a rare and intimate pleasure in a sub-genre usually devoted to extended fight sequences, serial villainous monologuing, and grand feats of magic or spiritual power. But don’t get me wrong — the fights are spectacular to behold.

Impressive Women Improve the Story

Balsa is not the sole incredible woman on this show. While the bulk of the cast is men — warriors and Star Readers in service of Mikado, the healer Tanda, and Prince Chagum among them — the characters who really shine are the women. Of particular note are Balsa, the Yaku magic weaver Torogai, and the Second Empress.

We have the Second Empress, Chagum’s mother and the second wife of the Mikado, to thank for the inciting action of the plot. Though seen on screen for relatively little time, she makes an impression. Far from being a submissive, fawning stereotype of femininity, the Second Empress is courageous and intelligent. Recognizing that Balsa has the best chance of defending her son from her husband’s misguided attempts on Chagum’s life, she pleads for Balsa’s help in the most effective way possible — she hires her. While her chosen method of payment is a heap of jewels and artifacts that would be almost impossible to sell discreetly, it speaks to her wit that she knows the fastest way to secure Balsa’s services.

By showing the lengths to which she will go to protect her son, the Empress demonstrates that she’s a woman of shrewd intellect. So, too, is Torogai, the Yaku magician who is Tanda’s mentor, Balsa’s sometime caretaker, and, for lack of a better term, a “healthcare consultant” for Prince Chagum. While Torogai is certainly what one would call “elderly” she is not frail or slowed by age. She has some delightful quirks, including single-minded attention to the pursuit of more information, a proclivity to speak openly and directly, and a love of good booze. Torogai has a frenetic vitality that makes her antsy and prone to act rashly. For that, she more often earns respect than critiques from her peers.

Torogai is also the show’s primary vector for information about Nayug, the world parallel to the familiar world of the human characters. Her knowledge of the creatures and spirits that make their home in that world proves invaluable in solving the mystery of the spirit possessing the prince. She is a woman who has achieved such a level of mastery in her field that she need explain herself to no one, and her skills are so well known that even the imperial family seeks her assistance.

Balsa, too, is a master of her craft. Perhaps the most compelling thing about Balsa is that she feels so fully developed. She has virtues and flaws that come from her innate character, not from her femaleness nor even her identity as a skilled warrior. She is dedicated to protecting lives without taking them, because of a vow she made to Tanda, and she is given to impatience and even outbursts of violence because that is what was modeled to her by her foster father, Jiguro. The tale of her youth alone merits an entire episode in the latter half of the series, and it is absolutely worth the wait to learn the full details of Balsa’s upbringing.

Even more compelling, Balsa doesn’t fit the mold of what a skilled warrior would be in this imaginary Shin-Yogo society. She’s a woman in a society dominated by men who have a monopoly on violence. She’s over 30 years old, in a society where women are expected to get married and settle down well before that age (there’s a whole episode about an overzealous matchmaker, though, thankfully, Balsa is not her target). And she is a foreigner to boot, coming from Kanbal. Yet at every turn, she earns respect for her prowess. Townspeople know her name, and speak reverently of her skill.

Even her foes respect her. In one of the best moments of the series, Balsa seeks out the services of a master swordsmith. He’s hesitant to offer aid because he knows she intends to fight, and possibly kill, the Mikado’s men. While she is there, the Mikado’s Hunters arrive to collect some swords, forcing Balsa and Chagum to hide. For a while, it seems the swordsmith may hand them over to their pursuers. However, when pressed into talking about his own skill as a warrior, Mon, the leader of the Hunters, tells the swordsmith that if ever there was a warrior worthy of the smith’s best craftsmanship, it is Balsa. After he departs, Balsa emerges from her hiding place and the smith agrees to forge her a new, better spear. Balsa doesn’t have anything to prove to anyone — her skill speaks for itself.

Politics, Violence, and Conservationism

While the nature of family ties and, yes, even romance are explored in depth on the show, Moribito delves into some even more heady topics. Politic and governance, and how they affect not just people but also the animals, environment, and landscape, make up the heart of the story.

The chief political power in Moribito is the Shin-Yogo empire, which is an analog to Japan. While, like Japan, Shin-Yogo is ruled by an imperial figure called the Mikado, who is aided by his noblemen and priests, the similarities to Japan go beyond the structure of the government. Like the Japanese, the Shin-Yogo people are not the original residents of their adopted homeland. That title belongs to the Yaku, who bear a passing resemblance in dress, culture, and beliefs to the Ainu, Japan’s aboriginal people who now primarily reside on the island of Hokkaido. While the two ethnic groups did have violent confrontations, the greatest damage came about when the Japanese government actively marginalized the Ainu community starting in the Tokugawa period, forbidding the use of the Ainu language, prohibiting Ainu from pursuing their traditional occupations, and later building schools intended to assimilate the populace.

While there is no overt violence between the Shin-Yogo and the Yaku, the show skillfully explores the tension between a colonizing foreign power and a less technologically advanced aboriginal power. The country’s founding myth greatly elevates the first Mikado while downplaying the significant and essential efforts of his Yaku companions, erasing them entirely from the official history. Consequently, the Shin-Yogo culture is so prevalent and monolithic that the Yaku are rapidly losing hold of their own cultural identity, which is, of course, revealed to be the very thing the heroes need to access to solve the mystery of what possesses Chagum. The message is clear: cultural erasure is a danger to humanity itself.

The Japanese government finally presented legislation this year prohibiting discrimination against the Ainu as a distinct ethnic group, an important first step in preserving their indigenous heritage. Perhaps, even inadvertently, media like Moribito and other popular works that deal directly with the Ainu, such as the manga/anime series Golden Kamuy, have had an effect on the national psyche.

Cultural aggression isn’t the only kind of violence up for critique. Though she is skilled with deadly weapons, Balsa’s overriding philosophy is one of non-violence. Concerned by the loss of life in her past, Balsa vows to never take another human life. Even facing insurmountable odds where striking a killing blow against her foes would turn the tide, she refrains, instead, disabling her opponents with carefully aimed strikes or overwhelming force. This philosophy is seriously tested at points, and Balsa must weigh her vow to defend Chagum at all costs against her commitment to never kill again on more than one occasion.

Non-violence in this case also extends to preserving the natural world. Balsa is committed not just to protecting Chagum, but also the water spirit he carries within him. Through that journey, we learn that the Shin-Yogo empire’s growth has had major effects on the flora and fauna. The show even goes so far as to describe elements of the food chain; frogs leap high out of the water to catch bugs, and birds in turn prey on those frogs by diving to catch them. The attention to these details betrays a very Japanese sensitivity to natural cycles and seasons of life.

Because of this sensitivity, Chagum’s concern for the environment around him is heralded as a virtue. His elder brother, Sagum, praises him for nursing an injured Nahji bird back to life, and he keeps the rehabilitated bird as a pet. Chagum also intervenes to prevent some children from playing a game where they swat leaping frogs out of the air, passionately explaining how it interferes with their feeding.

By contrast, the Mikado and his Star Readers are painted as self-serving schemers, and their obsession with preserving the political order at the expense of the natural order is ridiculed as a foolish vice. They would rather kill the prince than truly understand what he carries within him, and that tactic carries the potential for dire consequences. Their ignorance and pride could be the doom not only of their world, but the symbiotic, parallel world of Nayug as well.

All of these themes demonstrate the remarkable world-crafting feats that Uehashi and Production I.G have achieved. This world feels like a real world. Its characters, human and otherwise, are driven by compelling goals and are susceptible to mistakes and triumphs alike. It is governed by a convincingly daft political machine, it has rich and varied cultures, and it has a spiritual depth beneath the material surface.

Make Some Room on the Shelf

While the series comes to a satisfying conclusion, there is far more to explore for those who are curious. The world of Moribito is vast beyond the animated series. It is adapted from Seirei no Moribito, the first of 12 books by Nahoko Uehashi that her fans call the Moribito series. In addition to the original books in Japanese, the first two novels have been translated into English and adapted into a manga, with the sequel following Balsa’s journey back to her homeland of Kanbal. If anything, that second story, Moribito: Guardian of the Darkness, even more clearly expresses the folly of violence and how the loss of an individual can accelerate the death of a culture sometimes beyond recovery.

In 2016, NHK also started airing a live-action version of Moribito that had the grand ambition of adapting the entire 12 book series for a television audience. The third and final season of nine episodes aired last year, and the first few episodes of the first season are available on Amazon Prime in the US. With luck, more episodes will follow.

The wealth of additional material available is evidence of the story’s lasting appeal. Balsa and Chagum’s odyssey explores critical questions that deal with the bonds of family, the pain of loss, the responsibility we have to defend our environment, and the destructive nature of violence. For its cultural relevance, the beauty of its art, and the strength of its character performances, Moribito deserves a place in the great anime pantheon. It also deserves a place on your shelf.