The most recent live-action Disney+ Star Wars series, Andor received widespread acclaim for its more nuanced, mature look at the a galaxy far, far away. Fandom asked clinical psychologist Dr. Drea Letamendi to explore the man at the show’s center and what forged him.

Spoilers for Andor Season 1 follow.

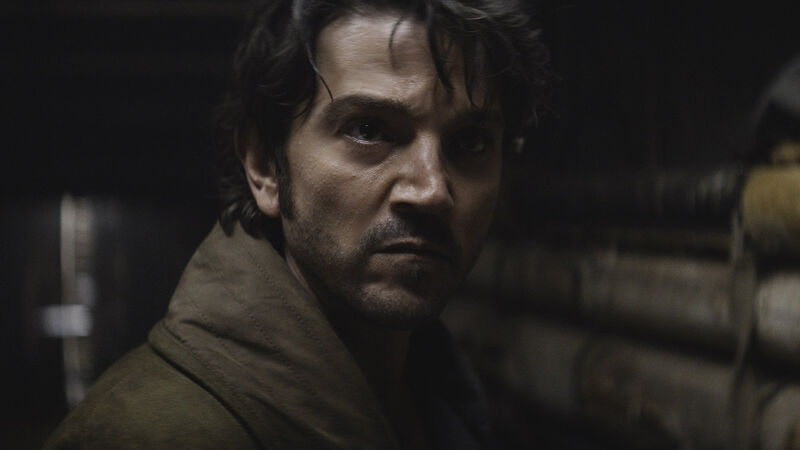

Cassian Andor knows he is unexceptional. Under his layers of laborer’s clothes, his roughened face and mussed hair, Andor can blend into the rain-soaked streets of Morlana One or slip into an Imperial Naval Base undetected. One of hundreds of scrapyard workers on the barren planet of Ferrix, Andor uses his ordinariness to achieve a repertoire of thievery, deception, and innocuous hustles. Adopted into a small family of salvagers, he’s known a life of quiet scrapping, getting by on untraceable trades and backroom dealing. He learned to speak sparingly, knowing he has an accent no one else shares. He learned to lie about his foreign origins, “passing” as an allegiant. He learned to keep his head down, fading out the daily indignities. He has few attachments, and most will rely on deceit, transactions, or contingencies. Andor’s ambiguous heritage and unimportant roots give him a sort of distorted social immunity: the invisibility of a working-class immigrant in a power-obsessed galaxy.

But in the increasingly dangerous era of Imperial siege, during the slow spread of intergalactic fascism, being common can be a vulnerability. It is nearly 15 years after Order 66, the government-led extermination of the Jedi, and the installation of the darkest shadow to ever engulf the galaxy: the Galactic Empire. In searching for his sister (they’ve been separated since childhood), Andor is more adrift than ever, and descends further into the hidden underworld of the mobilizing Rebel Alliance, taking riskier deals, partnering with anti-Imperialists, and discovering the brutal realities about the galaxy’s new suppressors. These formative years of surviving an intensifying revolution will transform Andor into the cool-headed, self-assured Rebel operative we see by the time his life comes to an end during the Battle of Scarif.

Cassian Andor — and the ensemble of activists taking part in the burgeoning Rebellion — show us the power of self-mutability, which is an adept way of navigating an oppressive socio-political system by moving through and between social spheres to achieve success. Andor, as a multicultural person, knows his identity is not fixed or static; it is malleable. Flexible. Intersectional. The self is a process, not an object. But might Andor’s constant chameleonic behavior get the better of him, make him forget who he really is? When does his self-erasure become no less oppressive than the fascists who seek to expurgate his culture?

Born in Obscurity

Andor was raised on Kenari, a small Mid Rim planet and the homeworld of a tight-knit group of indigenous youth who survived the occasional invasion of galactic conquerors and despoilers. Kenari was a resource-rich planet with lush jungles and mineral deposits, once sustainable and untouched by plunderers and exploiters. Andor grew up as “Kassa,” a member of the self-sustaining tribe and presumably the offspring of the native people who originally inhabited the planet. The Kenari civilization were autonomous, and disconnected from the socio-political happenings in the larger galaxy—their people were never subsumed or their land occupied during civil conflicts, and they did not have ships, comms, and droids to expose them to increasingly perilous cosmic wars.

As land caretakers, Andor and the surviving youth maintained a riverside settlement, spoke the Kenari language, and used the environment’s natural resources to build shelter, create clothing, and whittle weapons. (The Kenari language used by Kassa and his peers is not translated for viewers, creating the feeling of distance and exoticism). The fictional Kenari culture can be coded as indigenous peoples of Latin America; their clothing, jewelry, and warpaint used have the same colors and styles found in native Amazonian tribes. The Kenari weapon, the blowgun, is a ranged projectile with similar features as the “cerbatana” used by rainforest tribes in South America. The “kenari seed” is used in our world to craft percussive instruments and handmade jewelry, and can be found in trees that grow in tropical areas of South America. These real-world cultural associations signal Andor’s indigenous origin and concretizes the distance he feels between himself and the dominant culture he navigates.

The dwindling group of warriors dodge the perils of colonization up until the crisis that led to their eventual extinction: A starship crash-landing on their planet. Only an adolescent, Kassa joins the ranks of Kenari warriors to confront the strange voyagers. It shows a healthy eagerness for group belongingness. But the young Kassa doesn’t quite yet connect to the bigger meaning these early life relationships were meant to instill: the experience of a common, collective struggle toward a shared goal of liberation.

To his horror, Kassa witnesses one of the surviving soldiers shoot his tribe leader. Determined to learn more about these strangers, Kassa moves in on the wrecked ship, and descends into the control room from a hatch. He is curious, taking in the newness and the unfamiliar. But when Kassa notices himself in the reflection of a glass surface, he is overwhelmed with intense emotions. He attacks the console and machinery wildly, yelling in Kenari. It may be his first violent outburst, driven uncontrollably by frustration, pain, and devastation that presumably built up over the years of losing family to uninvited visitors. It is also the first confrontation with his duality. Seeing his reflection created a divided self, a child stuck between the traditions of his people and the seduction of his conquerors. He sees himself inside and in contrast to the technology that symbolizes the monster that would eventually annihilate his people. These are desperate, rageful cries directed at himself and the oppressive terror that he cannot yet see or understand.

The Scraps of Ferrix

Under the watch of the private security corporation Preox-Morlana, Ferrix is a dusty planet with salvage yards, junk landfills, and parts shops. In this working-class trading center, laborers spend their days stripping ships for resources and parts, repairing machinery, or renting out used equipment. Ferrix is home to all types of residents, various alien races, and immigrants who find work there. Dozens of warm-colored pairs of workers’ gloves hang on an exposed wall like punch-cards, depicting the diversity and individuality of the townspeople, in contrast to the uniformity and guardedness of the Empire.

Maarva Andor, a revered citizen of Ferrix, discovered young Andor when she and her husband Clem were salvaging a ship that had crashed on Kenari. Though Clem is unsure about taking in an orphan from the jungle, Maarva unequivocally decides to bring him on to their ship and take him home with them.

Though Maarva acted with complete genuineness when taking Kassa from his homeworld, she may not have realized the extent of the trauma he would experience by being grabbed, drugged, and carried onto her ship. Like the spare parts she smuggles, little Kassa is an unclaimed object that Maarva collects and transports. Though passionate and aspirational, Maarva unintentionally violates Kassa’s bodily integrity, establishing the start of a string of events that would make him question his personal autonomy and self-ownership.

Consequently, Kassa becomes Cassian, and herein begins his duplicitous life. Becoming a member of the Andor family would mean the erasure of his ancestral roots but it would also mean being pulled into a system of totalitarianism erupting on and around places like Ferrix. Maarva tells Andor he must lie about his past. He is to register as a traveler from Fest. Fest is referred to as an “urbanized” planet in the Outer Rim, densely populated and easily scapegoated as the homeworld of migrants and refugees. The fact that few people know about Kenari or even have met someone from Kenari underscores Andor’s constant feeling of displacement and disconnection. To the Corporate Conglomerate, Fest is unremarkable; Andor may convincingly look like someone who “made it out of the ghetto.” It is on Ferrix where Andor meets locals who he learns to rely on, including the savvy mechanic Bix Caleen and beloved family friend and fellow Grappler, Brasso.

Modes of Violence

“Violence is a personal necessity for the oppressed…It is not a strategy consciously devised. It is the deep, instinctive expression of a human being denied individuality.” – Richard Wright, Native Son

Andor is on the run because he murdered two corporate officers while visiting the planet of Morlana One. Andor did not set out or plan to kill these armed men–they spot him inside a brothel, then follow, harass, and beat him. Andor stays calm and offers to pay them off, and while being searched, he manages to wrestle a gun from one guard and shove off the other. It is sloppy. When he realizes the fallen guard had sustained a fatal blow to the head, he knows it is a life-or-death situation. As Andor stares at the defenseless guard, a mental commitment turns to action. He points the pistol and kills the remaining guard at close range. This is a turning point for Andor; he may have used defensive violence in the past, but the incident with the Corpos triggered a more calculated and level-headed engagement of violence.

Violent behavior isn’t only about observable actions; context matters. Criminal and forensic psychologists denote violence as having a “bimodal classification.” That is, there are two main types of violence – Affective and Instrumental. Affective violence includes actions that are defensive, unplanned, impulsive, and emotional. This kind of violence serves to reduce a perceived immediate threat. It is even considered natural. Imagine a housecat with its ears pinned back and body arched. We are all capable of affective violence because it often emerges as a result of subjectional emotional experiences such as fear or anger. In humans, it’s a hard-wired reaction as a result of severe abandonment, rejection, and abuse, or really anything that can threaten our survival. Kassa’s aggressive outburst in the crashed ship on Kenari is a good example of Affective violence; he lashes outward because his inner, biological state is alerting him to danger.

Instrumental violence, in contrast, is typically controlled, premeditated, and unemotional. Members of the Empire’s Internal Security Bureau (ISB) employ repeated and orderly violence in the form of excessive labor, prisoner’s abuse, torture, public hangings, etc., with little emotional drive save for the salient motivation toward conquest. Over a decade of exposure to political violence may have desensitized Andor to a certain type of ruthlessness, but the event on Morlana One is a precarious start to his pathway to targeted violence. The way he reacts to the guard’s suggestion that they turn themselves in shows Andor is not panicked or frozen; he is quiet, working through the potential outcomes that do not result in his death. With the weapon aimed at his assailant, there was no screaming, yelling, or pleading from Andor. No, he did not set out that night to kill these men, but he has been prepared to engage in goal-directed violence.

“So let’s not get emotional.” – Cassian Andor to Bix Caleen

Instrumental violence can sometimes seem just or necessary. However, it is common among psychopaths—people with shallow feelings, proneness to boredom, remorselessness. Bombers, arsonists, and stalkers of public targets tend to engage in this emotionless type of violence, and can make effective political insurrectionists if they detach emotional connection from the victims who get caught up in their destruction. It is possible that the deadly scuffle on Morlana One fulfilled a sense of agency or empowerment within Andor, when in his past he reacted out of helplessness and fear. He was once too passionate and impulsive, but he’s learning to keep a cool head when under fire.

Ni de Aquí, ni de Allá

(“From neither here, nor there”)

Andor believes his ticket out of Ferrix and into safe seclusion is the valuable starpath unit he’s stolen from an Imperial Naval Yard. Through Bix’s black-market connection, Andor finds a buyer: Luthen Rael. Luthen is a mysterious and solemn revolutionary who traverses the galaxy to organize a rebel network and spy operation for the Rebellion. There are many faces of Luthen. He is a man of theatrics, pantomiming an eccentric, carefree shop-owner who indulges in rubbing elbows and gossiping with the wealthy, as a front for collecting intel for the Rebellion.

A masterful deceiver himself, Luthen is impressed with Andor. He’s gathered enough information about Andor to learn about his craftiness, resilience, and risk-taking. Luthen knows about Andor’s early troubles too, his encounters with the law, his juvenile delinquency, his arrests. He knows that Andor’s adoptive father, Clem, was hanged in the town square by Clone Troopers when the first military occupation of Ferrix began. Luthen is astutely aware Andor may be vulnerable to radicalization given these characteristics: extreme personal losses, deep disillusionment with the government, and nothing to lose. When Luthen asks Andor to explain how he managed to steal a valuable piece of Imperial technology, Andor reveals a critical part of himself: he uses the ideology of his enemy against them.

“You just walk in like you belong. They can’t imagine it… That someone like me would ever get inside their house, walk their floors, spit in their food, take their gear.” – Cassian Andor

Ni de aquí, ni de allá is a common phrase used in Latino-American communities to describe the life experience of “in-betweenness.” Directly translated, it means “from neither here nor there,” but it has larger meanings. It’s the pressures of navigating two or more cultures while also not being recognized as being a full member of any culture. It’s the feeling of being a perpetual foreigner even though one is home. Multicultural identities are often seen as threats to the fascist state because they cannot be coded or categorized, cannot be limited to borders, nations, or races, the constructed conceptual foundations rooted in epistemologies of power, privilege, and oppression.

The Empire spreads and approves the ideology of xenophobia, classism, and racism, which manifests at individual as well as systemic levels. Andor experiences discrimination and prejudice because of his marginalized identity. Law enforcement call for his search and arrest, canvassing for suspects with “dark features.” The Morlana One sentry guards who harass Andor taunt him with, “you swim over, scrawno?” which is a denigrating comment similar to the “wet” racial slurs often used toward lower-class immigrants in the U.S. whose languages, accents, bodies, and lifestyles do not fit the characteristics of the dominant white culture. These communities are expected to take menial and physical labor; construction, repair, waste management. Andor explains to Luthen the realities of people who look like him. You just walk in. His point is that, aside from the occasional indignity, people in power do not choose to notice him.

Holding two or more cultural identities is both historically and institutionally undesirable, but economists, psychologists, and cognitive scientists promote the value of multiculturalism. Andor, for instance, has learned to harness strengths from his multifaceted identities. He adapts and functions effectively across social environments. He leads us to look beyond his “criminal” identity to then value the strengths of his social intelligence: switching, shifting, flow, and discernment. In contrast, the purist Imperialists pursue a self that is static and similar, attempting to preserve an identity that is unmoving and unchanged no matter where they go.

Behavioral adjustment is called code-switching, a strategy that People of Color and Indigenous individuals use to navigate interracial interactions. Code-switching has large implications for our well-being, economic advancement, and even physical survival. It involves adjusting one’s style of speech, language, appearance, behavior, and expression in ways that elicit the comfort of others—usually people in power—in exchange for fair treatment, employment, and, again, even safety.

Code-switching is an approach that can help individuals reduce otherness or downplay membership in a stigmatized group; we learn to align ourselves with the dominant culture for better treatment. Andor literally changes his indigenous name and lies about his country of origin in order to blend in. On the other hand, code-switching is also used to amplify community belonging. The people of Ferrix act differently in front of the Imperial guards than they do when exclusively among each other. The sharing of customs and processions that are meaningful and unique to the Ferrix community offers them the visibility, honor, and affirmation that they simply cannot receive from their occupiers.

But code-switching comes with a cost, in the form of internal dissonance, disequilibrium, and survivor’s guilt. Dodging stereotypes is fatiguing. Feigning commonality reduces authentic self-expression and contributes to burnout. As if to remind us of the exhaustion of performing multiple selves, Andor’s droid B2EMO plainly states that it takes extra energy to create a distorted narrative: “I can lie; I have adequate power reserves.”

False Narratives

Luthen appeals to Andor’s desire to wound the Empire, but clenches the deal through Andor’s bigger desperation for money. The heist takes place on Aldhani during the night of the Eye, a cosmic event celebrated by the native Dhani community who take pilgrimage on this special occasion. Experienced in espionage and subterfuge, the band of insurgents show Andor that their way of life is completely folded into the Resistance. To Andor, it’s all just a “job,” but the idealistic and hopeful Karis Nemik, the astro-navigator of the team, nudges deeper into Andor’s belief system. Nemik is an “all-in” Rebel, showing Andor his unwavering conviction that everyone matters and makes a difference in the fight against fascism. Even if it means dying for the cause.

Andor effortlessly takes on an alias, Clem, the name of his adoptive father. His training on Aldhani reveals his gifts of observation and discernment, and despite revealing to the team that he’s working as a mercenary, he has earned their trust. As their pilot, Andor is a critical part of the successful raid and narrow escape. But it is followed by immediate betrayal. Arvel Skeen abandons his crewmates and secretly offers Andor a cut of the payroll he plans to make off with. Andor acts with little hesitation, unfazed that disloyalty, duplicity, and greed is not exclusive to the Empire. Left with no good choices, Andor kills Skeen with one fatal shot.

The Empire speaks with little euphemism, calling out “disease” as a blatant metaphor for economic, racial, social, and ideological contaminants. Major Partagaz, a high ranking leader of the ISB, lectures his staff with the pedagogy and philosophies of ultra-nationalism, showcasing the systematic ways science is distorted to assert cultural, intellectual, and emotional inferiority of marginalized people.

“We identify symptoms. We locate germs whether they arise from within or have come from the outside. The longer we wait to identify a disorder, the harder it is to treat the disease.” – Major Partagaz

Fascism is the catastrophic disintegration of democracy, and it can spread quickly. The mounting Empire, blanketing the galaxy with its unvarying grey-and-black color scheme, its militarized architecture, controlled vistas, and homogenous followers, subordinates individual interests for the perceived good of society. It is a system of sameness. The Empire operates, both directly and indirectly, to squeeze out differences. Andor’s community on Ferrix represent the preservation of culture, whether through organized social clubs such as the Daughters of Ferrix or informal shared practices like the banging of metal to amplify voices.

In contrast the Empire erases, exploits, and desecrates culture. Imperials capitalize the spiritual customs of the Dhani. They weaponize the cries of children of the Dizonite species by turning them into torture devices. And — as performed and ventriloquized by Luthen himself in his purposely pretentious shop of exotic gifts — they exploit the belongings and histories of massacred and exterminated cultures. From rare mythical tablets to Jedi holocrons to Mandalorian Beskar armor, Luthen’s artifacts are the playthings of hobbyists and elites. He indulges the fetishization of cultural, intellectual, and spiritual property. When Senator Mon Mothma visits Luthen’s antiquities gallery, he tells her to “free her mind.” He explains that it is hard to be surrounded by such history and “not be humbled by the insignificance of our daily anxieties.” His comments hint a back-handed subtext. Coded in his overly cheerful remark is a reference to their double lives, a stern reminder to remain focused on the welfare of the communities they are trying to liberate, and a warning that while he must return to bloodshed, Mon Mothma can easily get lost in the privilege of her comfortable estate on Coruscant.

“Calm. Kindness, kinship. Love. I’ve given up all chance at inner peace, I’ve made my mind a sunless space. I share my dreams with ghosts … I’m damned for what I do.” – Luthen Rael

The Survivor Personality

While laying low on Niamos, Andor is arrested for vandalism and anti-Imperialism speech. He’s sentenced to 6 years at the maximum-security prison located on Narkina 5, where detainees are forced to work 12-hour days assembling undisclosed machines for the Empire. Both a prison and a factory, the complex has little to offer toward actual rehabilitation. The dehumanization of the inmates occurs by physical control; the guards use electrocution as punishment. Laborers spend their years growing exhausted, are worked to death, and some are so depleted that they die by suicide. Andor and his floor manager Kino Loy learn that inmates are never freed after serving their time, but simply relocated to a different unit in the prison—they are but cogs in the machine, as disposable and replaceable as cheap parts they are assembling. With the help of Andor’s strategic planning, Kino and Andor lead an organized resistance force and stage a colossal prison break.

“If we can fight as hard as we’ve been working, we’ll be home in no time.” – Kino Loy

At the mouth of the prison, looking out onto the vastness of the ocean, Andor basks in the exhilaration of true freedom. Breaking out was a coup for the thousands of prisoners destined to die there, but it is also a breakthrough in Andor’s ideology. He knows to attack the Empire from within its own tyrannical system, he knows to leverage the tools of the enemy to defeat the enemy. But he realizes the labor prison is a microcosm of life under the Empire’s rule. A single individual cannot simply “get out;” they will only be returned to another trapped circumstance. A true revolution comes in the form of collective liberation. Significant change can be made when the masses realize the power of their numbers. By destroying the prison’s security, disarming the guards, and commandeering the control room, the inmates reclaim ownership of their bodies, minds, and spirits. This instrumental violence, when aimed at the structure, practices, and people who perpetuate oppression, is an undeniable feature of social justice. Andor has worked with others before, but the unity felt among his fellow prisoners sparks a passion within him. Not everyone makes it out of the prison alive, but they all conclude that death during an act of rebellion is preferable to a life made complacent under tyranny.

“I’m condemned to use the tools of my enemy to defeat them.” – Luthen Rael

A core feature of the survivor personality is adaptability. Andor’s draws information from his environment and aligns himself to his context, skills that allow him to overcome unexpected hardships. Survivor personality traits include being habitually curious, showing a readiness for challenge, harnessing the ability to surmount crises through personal effort, and emerging from tough experiences with previously unknown strengths. Self-determination is a key component for a healthy survivorship mentality—Andor begins to see himself not as a helpless victim (of false arrest, imprisonment, or racialized discrimination) but as a whole person with control over his destiny, despite the inevitable occurrence of future setbacks, losses, or pain.

Andor, constantly on the run, always adrift, finds himself a little less lost in the universe. After the prison break, he begins to build something called critical consciousness which is a person’s capacity to thoughtfully reflect and act upon their sociopolitical environment. Sometimes it is referred to as “waking up,” because it involves a personal transformation, removing the veil of complacency, morally rejecting real-world oppression and inequity, and seeing oneself as able to facilitate change. Critical consciousness involves moving from ideological commitment to action, usually undertaken with others, to reduce or slow the spread of oppression. Research shows that engaging in social action and activism can increase psychological well-being by enhancing a sense of empowerment, giving purpose and offering a more salient identity.

“The Empire is a disease that thrives in darkness. It is never more alive than when we sleep. It’s easy for the dead to tell you to fight …But I’ll tell you this. If I could do it again, I’d wake up early and be fighting these bastards… from the start. Fight the Empire!” – Maarva Andor

Fighting the Empire takes much more than one lucky shot. The cast of characters around Andor tells us that resistance must take many forms, and span subterfuge, sabotage, infiltration, boycott, protest, divestment, and, as even the idealist Nemik suggests, even more extreme strategies of disruption such as instrumental violence. When activism not only has true connections to our values, to our strengths, to our cultural authenticity, but actually leads to reducing real power inequalities, there is potential for these actions to reduce our suffering. We call this work transformational psychopolitical validity (TPV), when our involvement in systemic change can help promote our personal, relational, and collective wellness.

Rebellions are Built on Hope

The Imperial forces are now occupying Ferrix. The uniformed troops have established a curfew, and all transmissions are intercepted. Turrets are set. A public funeral procession is planned in Maarva’s honor, and the Empire chooses this ancestral custom to lure Andor in. As Bix is being tortured by the ISB, the troops assemble on Rix Road, and tensions rise. Returning to his home a fugitive, Andor can no longer look away from the brutality and cruelty of the Empire. He has, as Maarva will posthumously attest in her speech, woken up. His reckoning has set in: Reclaiming your freedom is nothing less than a radical act when you exist in a system that sees you as less than human.

Healing from the trauma of oppression caused by poverty, racism, and class exploitation is in of itself a psychological and political movement. The problem isn’t inside of us. Healing requires outward forms of reconciliation, such as shared testimony and actions that hold systems responsible. Radical healing, a psychopolitical framework for BIPOC people, moves away from the “deficit-based” perspective of mental health interventions. Radical healing fosters a sense of agency to challenge and change oppressive conditions. Though it blurs our concept of heroism, we can understand how amputating resources (the Aldhani heist), destroying mechanisms of oppression (the prison break), and fighting in an uprising (Rix Road) are perilous but also reparative aspects of Andor’s traumatic healing.

Staying in either extreme—the despair of oppression or the fantasy of possibilities—is detrimental to one’s mental health. When it comes to psychological strength, the framework of just being “more positive” doesn’t always work. It doesn’t account for racism, xenophobia, and other forms of disparagement directed toward marginalized people. However, those with a survivor personality can employ a realistic sense of hope that is attached, or grounded, in the world they live in (this is termed radical hope by psychologists).

Wartime hope allows for a sense of agency to change things for the greater good—a belief that one can fight for justice and that the fight will not be futile. It is an especially helpful paradigm for groups experiencing cultural devastation—here, certainly the people of Ferrix as they take to the streets to face yet another military occupation. They show up authentically, boldly, their march deeply rooted in ancestral tradition. Whatever the outcome, they assemble with unity, self-definition, and metaphysical interconnectedness.

Kassa learned early in life to hate the scrawny dark boy who looked back at him in the mirror. Maybe it took becoming Cassian, Clem, the alias “Keef” and other personas to realize that he was trying to get out of his trauma by recreating his place in the world. His healing will only come when his actions are authentic, reflect his truth, and align with his identities. It is perhaps why he chooses to join Luthen as a Rebel operative, with uncertainty about what the future holds for him as well as an openness to learning how he fits within the overall cosmology in which he exists.

Cassian Andor’s story is gritty and solemn, and it’s told without the distraction or relief of lightsabers, magical forces, and little green puppets. Enduring alongside Andor can resonate for viewers who will sit with themes of invisibility, social mobility stress, and uninterrupted vigilance. Whereas Luke Skywalker yearned to be free of a life of mundaneness, Cassian Andor struggled to simply exist freely as himself in an ordinary world. His fight for freedom is hardly a concept far, far away.