“Twenty years ago today…”

These are the words that kick off one of the strangest, campiest, and funniest games ever made: Maniac Mansion. First released in 1987, this innovative point-and-click adventure game revolutionized the genre and entertained players for years to come. With a cast of seven playable characters and a plot that included talking tentacles and scheming meteors, nothing quite compares to Maniac Mansion.

25 years after its initial release, we look back at the history of this one-of-a-kind creation.

Maniacs and Kings

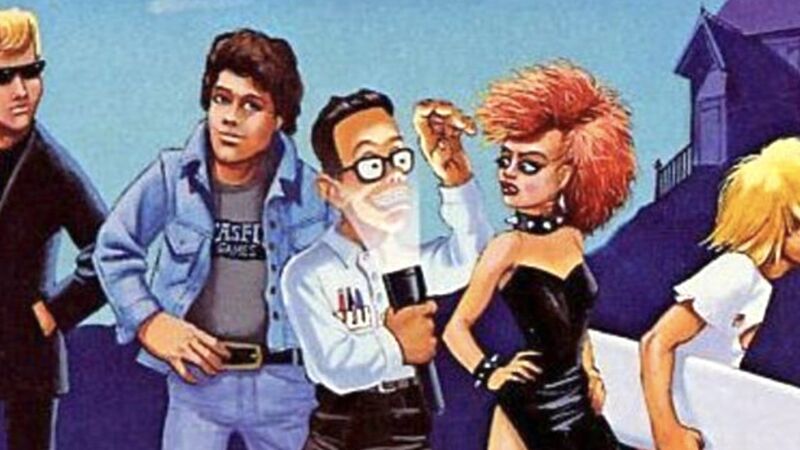

Maniac Mansion tells the story of Dave, an average teenager who (along with a few close friends) must rescue his kidnapped girlfriend, Sandy Pantz, from the maniacally mad scientist Dr. Fred. Dave and two other characters of the player’s choice enter the game’s titular mansion, a house inhabited by Dr. Fred and the rest of the extremely strange Edison family. Through exploration and clever use of the mansion’s environment, players must solve a series of story-based puzzles to save Sandy.

It’s not entirely fair to call Maniac Mansion’s publisher, Lucasfilm Games, a fledgling company—it was founded by famed director George Lucas (you may have heard of him) as a spin-off of the Lucasfilm Computer Division. However, through the company’s early days, it was serving solely as a developer, meaning that most of their products were going to another publisher. By 1985, the decision was made to develop a unique product that Lucasfilm Games could self-publish, allowing it to stand independently.

Enter programmer Ron Gilbert and artist/animator Gary Winnick, friends and coworkers at Lucasfilm Games who took on the task of making a new game with gusto. Talking at length about their approach, they connected on the idea of building a game inspired by classic B-movies. Getting the tone right would be important: a mix of self-seriousness and campy, sardonic humor. They weren’t afraid to pull from real life either. The pair liberally took setting ideas for the mansion from Lucas’s own Skywalker Ranch, stole plot elements from movies they’d seen, and based character concepts on friends and loved ones.

However, even though they had the key elements of the game decided, they still didn’t quite have an idea on how to put it all together. Then, a stroke of luck happened, making Maniac Mansion possible and driving a full decade’s worth of games in the process.

Gilbert was visiting family when he first encountered King’s Quest. The King’s Quest line was a series of graphics-driven adventure games made by Sierra Online. Most adventure games to that point had been text-based: players were given on-screen prompts and then interacted with the game world by typing commands into a text parser. King’s Quest added a visual element, allowing players to navigate and investigate the world more freely; however, commands were still entered into the parser.

Drawn by the idea of a graphic adventure game, Gilbert started working on Maniac Mansion’s most important contribution: the SCUMM engine.

SCUMM and Villainy

What made SCUMM (Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion) stand out was its innovative point-and-click interface which used preset verbs and objects to drive gameplay. Functionally, Maniac Mansion worked on the same premise as a text parser: players had to determine the correct answer to a given puzzle using specific commands. However, now they had a list of always-available actions to choose from, which they could use to interact with inventory items, on-screen locations, and characters. With straightforward verbs like OPEN and PUSH, SCUMM took the guesswork out of the gameplay. Players could more easily think through the logic of a given situation, using the tools provided to arrive at the solution.

This was particularly important because of Maniac Mansion’s central conceit of playing a team of multiple characters, with each character having unique options. All three chosen characters would use the same verb set, enabling the player to seamlessly switch between them. Because of the way it was programmed, SCUMM also allowed characters to easily stand in for each other so that a given moment of gameplay would look the same regardless of which character was active.

As a bonus, this gave the programmers the freedom to incorporate more narrative elements. While Maniac Mansion wasn’t the first game to use cutscenes, Ron Gilbert is credited with coining the term—and with good reason. Maniac Mansion uses cutscenes to excellent effect, both to explain and drive the plot. Some cutscene events only occur after a certain time or trigger, giving the game the brisk pace of a film.

Another advantage of SCUMM was that it was relatively simple to edit and update, allowing for rapid prototyping and easy cross-platform use. This would be a massive boon to the production of Maniac Mansion. When David Fox was brought in to work on programming the game’s events, the team could work fluidly and organically, adding new elements without having to rework the whole system.

The SCUMM engine was so effective that it would become a major part of Lucasfilm Games (later LucasArts) going forward. The company followed Maniac Mansion with Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders in 1988 as well as Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure in 1989, though it would gain larger acclaim with The Secret of Monkey Island in 1990. Several more hits followed through the ‘90s, perhaps most notably Maniac Mansion’s sequel Day of the Tentacle in 1992. However, as consoles started to dominate the market, interest in adventure games waned, causing LucasArts to eventually move away from adventure games completely after 2000’s Escape From Monkey Island.

Console Crossover

Of course, Lucasfilm Games took advantage of the console craze when it partnered with Jaleco to bring Maniac Mansion to the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1990. (Technically there were two NES versions; one was released only in Japan with significant changes and isn’t representative of the original.) This would prove to be a major problem, as the game’s cheeky comedy didn’t mesh well with Nintendo’s family-friendly vibes

Unfortunately, Nintendo’s content guidelines weren’t entirely clear or consistent. The Lucasfilm Games employee in charge of shepherding the conversion, Douglas Crockford, went back and forth with the censors trying to find the line between subtle innuendo and inappropriate content. Some changes, like switching “pissed” to “mad,” were fairly obvious and easy. One even improved the game; it’s hard to argue that Dave telling Bernard “don’t be a shit head” is funnier than the Nintendo version’s “don’t be a tuna head.”

Others required more finesse to keep the game’s original tone while still meeting the censor’s concerns. The character of Nurse Edna (the Edison matriarch) saw major revisions to pull away from the sexually suggestive dialogue and situations that defined her character. Gone were the lecherous comments when she discovered a teenager in the house and the reference to heavy breathing when a character telephones her. Graffiti that implied she was promiscuous (“for a good time Edna 3444”) was rewritten. Similarly, dialogue that unintentionally implied that Dr. Fred was a cannibal rather than a Frankenstein-like character had to be changed, along with a few background images like an arcade machine named Kill Thrill (which eventually was given the much weirder name of Tuna Diver).

The most confusing, though, was Nintendo’s concern over something that should never have been contentious. In the credits of the game, the “NES SCUMM System” is referenced; quite obviously, this is referring to the engine that the game runs on. However, Nintendo felt squeamish about how “SCUMM” might be interpreted, so, just like that, one of the game’s most defining features was removed from the credits.

On the plus side, the Nintendo release was the only one that included background music. Each character’s inventory now featured a CD player which automatically played their signature tune and could be turned off to mute the song. With multiple references to music throughout the game—the playable characters Syd and Razor are both aspiring musicians, and the Green Tentacle who lives in the mansion can be bribed with a recording contract (obviously)—the addition of unique music helped bring the weird world of Maniac Mansion to Nintendo’s broader audience.

But Wait, There’s More!

That said, it’s not entirely clear whether Maniac Mansion could ever truly appeal to a broader audience. The game’s offbeat style just wasn’t for everyone, though it drew its fair share of passionate fans. Perhaps the strangest attempt to take it to the masses was the release of the Maniac Mansion TV show, a curious affair created by SCTV’s Eugene Levy and broadcast simultaneously on Canada’s YTV and America’s Family Channel.

While Levy headed up the show, its genesis came from animators Cliff Ruby and Elana Lesser. The original premise was to lean into the game’s B-movie roots to create an unusual episodic science fiction comedy. In Levy’s hands, however, it drifted into a more traditional family sitcom style that relied heavily on Second City veterans. Despite the fact that it was only loosely connected to the game, the show ran for three seasons (from 1990-1993) and received fairly positive reviews overall.

More successful was Maniac Mansion’s sequel, Day of the Tentacle. Frequently cited as one of the best adventure games ever made, Day of the Tentacle features several characters from the original but leans heavily into time travel to create its puzzles. In a fitting Easter egg, the entirety of the first game can be played on a computer within the sequel, bringing the Maniac Mansion saga to a satisfying close.

Maniac Mansion’s true legacy isn’t just in the story of its development. The creation of the SCUMM engine changed the course of adventure games entirely, pushing them in a new and bold direction. That genre has continued even through today, with the lasting careers of Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick (and the excitement over the recent release of Return to Monkey Island) as proof of its popularity. Like the meteor that lies in Dr. Fred’s basement, Maniac Mansion continues to exert its influence long after its initial impact.