Full motion video (FMV) games have had a bad rep for the last 25 years — ever since the combined mediums of game and film were thoroughly abused by Night Trap on the Sega CD. But Square Enix is trying to set that right with The Quiet Man. Amidst a resurgence of FMV games, with the likes of Her Story, The Infectious Madness of Doctor Dekker, and The Bunker, their effort is looking to take things to another level, seamlessly blending video with photorealistic graphics.

Rise of the Full Motion Video

“It’s always a challenge to have this live-action thing,” said Producer Kensei Fujinaga. “But then we also want to have the game be very, very photorealistic and to blur the line between the live action and the very real CGI. [It’s about trying to make the line disappear], and again, it’s coming very close. So yeah, we felt like it was a good chance, a good time to give it a try again!”

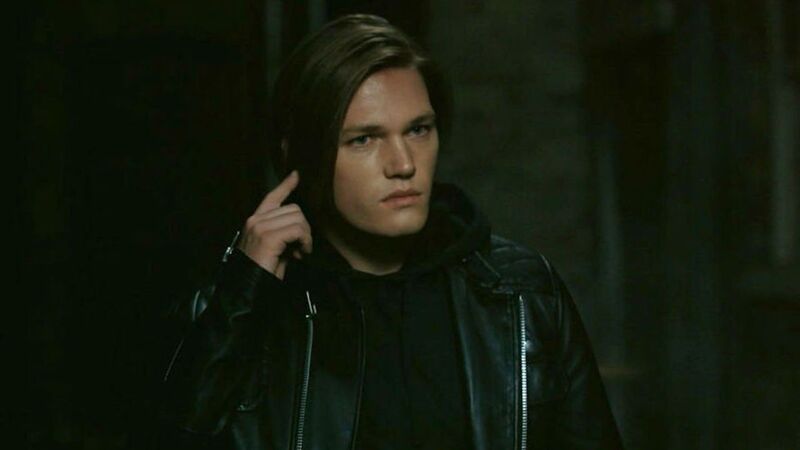

The Quiet Man tells the story of one night of Dane’s life. It’s not a particularly good night for him, which sees him have to fight his way across New York City. As Fujinaga explained, it’s a pretty straightforward tale: “The only thing you know is he’s a bit quiet, and he doesn’t hear. The story about The Quiet Man is all about just one night when this Songstress gets kidnapped by this mysterious masked man and Dane wants to get her back. That’s about it. That’s how simple it is!”

With that in mind, it’s also rather short and to the point. It’s set to weigh in at around 3 hours and will be priced at $14.99. “This game has Square Enix’s name on it, but it’s so indie-minded, it’s so independent,” Fujinaga told us. Yet it has a team that spans the globe with four separate studios working to develop it. The small team at Square Enix isn’t just joined by a film crew — Live Action Team Leader Shuichito Hamada has worked with Fujinaga on games for over a decade — but also the U.S.-based Human Head Studios and 3Lateral Studios.

Playing With Cinema

Talking about Human Head’s role, Art Director Ashley Welch said it was “definitely a collaboration. We got a head start with what the vision was, what the story was. The live-action team did a lot of casting and wardrobe and location scouting stuff. So, our role was supplementing that so that the parts that didn’t overlap we ran with, and then we worked with them really closely to digitise their world and recreate it in the game.”

In the end, it’s all about making the shifts from video to game practically seamless, even if you can see the difference in quality once the jump has been made. Every single scene had to be scanned prior to shooting, all of the actors had to be digitally recreated, the particle lighting and colour coding were reproduced, and on and on. Lead Environment Artist Randy Rudetske recalled, “I remember the moment we realised we were scanning props that were actually not real, they were fabricated. It was an interesting moment for us …” And yet Welch said, “I was surprised. It was very complicated, not simple, not easy, and very challenging, but I was surprised at how well it worked.”

In a lot of ways, it’s an effort that isn’t too far away from modern CGI-infested cinema. You often see the behind-the-scenes videos of actors trying to be as serious as possible while surrounded by green walls or action sequences that have people leaping between “rooftops” that are added in post.

Sounds About Right

The snippets of gameplay we’ve seen so far look fast and impactful, sensationalised to give an added speed and weight seen in many Japanese action games. However, it has to feel right without one of the key components in a game: sound. Sound tells you how fast the car you’re driving is going and what a character is feeling. It adds weight to every gun you fire, every punch that lands.

Fujinaga recalled: “Actually, the very first person I talked to when I decided to make this game was a sound director because the sound design is essential for game design to give the feedback to make the visuals work. So instead of doing all those normal sounds, we have tried to create Dane’s version of them. He does not hear, but he is not living in the world without any information. He has feedback, but they are physical, so we tried to create his version of those sounds for those impact moments, heartbeats, footsteps, to be for him, his world. It’s not the usual sound effects. Anything that he feels with his body has to be heard with a very unique, well, you know… It’s very hard to describe!”

Let’s give it a go anyway: It’s like when you wear closed headphones and are able to hear your footsteps, or when you’re trying to get to sleep but all you hear is your heartbeat, or when you dunk your head underwater and try to shout. There’s a muted tone to the sounds shown in the game’s trailers that feels reminiscent of these kinds of things.

Yet the deaf and hearing impaired community still need to be taken into consideration. Welch explained: “We had to put more into it visually because if we couldn’t speak to it visually or through something vibrationally and tactile, then we can’t have it in the sound either. There was almost a filtering process there, where we might want to put something into the sound but if we can’t complement it for the other portion of the audience, then we wouldn’t go with it.”

The Kojima Conundrum

Striking a balance between cinema and game, The Quiet Man will lean quite heavily on the former. “I would describe our game to be an interactive cinema-like experience,” Fujinaga said. “There are a lot of watching parts, and it was designed to be just like watching a film and have some combat and interactive moments to it.” And yet there’s still a very important side to the game’s pacing, where he rightly observes that “it’s just like watching in the cinema; if it’s just one hour of fighting, that breaks the drama.”

There’s an awful lot of moving parts to The Quiet Man’s development, and I can’t help but feel that if one of them comes loose, the experience as a whole could falter. If the balance between cinema and game is off, if the shifts from video to fighting or exploring don’t feel natural enough, or if the game graphics end up in the uncanny valley, it could turn from a bold new experiment into an echo of ’90s FMV.

That’s almost certainly part of the excitement for Fujinaga and the team: “We really wanted to make a new form of game, a new style. That’s why we always feel that this is so indie because we’re trying to be so different from what’s always been done. I was like, ‘Let’s try something crazy, something so different!’ That’s the challenge!”